The first females to ride around the world

The first females to ride around the world

Happy women’s history month. Which only gives me another reason to write about more incredible humans that also happen to be female. What fascinates me most about the stories of the women I’d like to share with you today, is not that they dared to figure out how to ride a motorbike or infiltrate a culture heavily dominated by male protagonists. It is more so their innate bravery to ride into the unknown, across the world– without the safety of a partner, without the comfort of technology or the reassurance of previous trailblazers to show them it was even possible. These women’s names and stories and faces need to be remembered and retold over and over again. For their fearlessness is our fuel for a better future. So let’s ride…

It was Elspeth Beard that first lead me on the hunt for female riders who faced the road alone. Here’s her story in the tiniest of nutshells: At 24 years of age, she became the first Englishwoman to ride a motorcycle around the world, a journey spanning 3 years and 54,000km in 1980.

With her 1974 BMW R60 that she’d saved up to buy while working in a London pub, she began her journey in New York City, having shipped the bike from England.

After travelling through Canada, Mexico and California, Elspeth shipped her bike to Sydney, then to Singapore and Thailand where she had an accident and recuperated with a local family that took her in.

She forged a permit to get into Pakistan, before riding back into Europe via Turkey. Elspeth is my breed of adventurer, and I think you’ll find she speaks our language when it comes to her idea of travelling:

“For me the journey isn’t riding a bike,” she told VCC in a filmed interview with the womenswear motorsports brand. “The journey is what happens, the experiences, the people you meet, the locals you meet. If you’re fixed on following this blue or pink line on a [] screen … you don’t have to stop and ask people the way…”

“I [used to] have some great (time) where I would to stop and ask locals and then they’d ask me in for a cup of tea and then I’d end up staying the night. Those kind of things don’t happen to you if you’re fixating on following a line to a hotel that you’ve booked on a bloody phone.”

Before she set off on her journey, Elspeth had tried to get some interest from the bike press world, but was met only with chauvinism, skepticism and disinterest in her Endeavour. It’s only recently that her incredible story has even become public knowledge, thanks to her decision to write a book about her journey.

“My story– a box of my diaries, my journals, everything–sat in a cupboard for 30 years […]. It was a part of my life … that no one was ever going to know about.”

“My story– a box of my diaries, my journals, everything–sat in a cupboard for 30 years […]. It was a part of my life … that no one was ever going to know about.”

But I wondered– how many other stories like this have gone untold?

Meet Anne France Dautheville, French journalist and writer, both fearless and glamorous, who in 1973 at the age of 28, may have become the first woman ever to ride solo round the world on a motorbike– assuming there aren’t other riders yet to share their tale.

Riding a Kawasaki 125, she covered 20,000 km on three continents. Three decades later, she received an email from French fashion house Chloé asking her to be the muse of their 2016 collection. With renewed interest in her story, a New York Times article shares some anecdotes from Anne France’s travels:

She’s flagged down by a car, and three children get out to ask Dautheville about herself, her life and her eye makeup. (“I always made up my eyes,” she recalls.) “Then they start driving faster than me. Ten kilometers later, they stop on the side of the road, and they stop me again. I ask, ‘Is there something you forgot?’ And they say, ‘Well, we were wondering, are you a girl or are you a boy?’ ” Dautheville throws back her head and roars with laughter.

Asked if she was ever afraid travelling alone she replied: “Yes, but eventually I discovered the solo woman is extraordinarily protected. In Afghanistan, for example, one day I had a puncture. I saw three guys get off a truck. There is one who takes me by the shoulders and makes me sit, the second starts in front of me to make me shade and the third repair my tire! It has probably changed since, but I belong to a time which was amazing.”

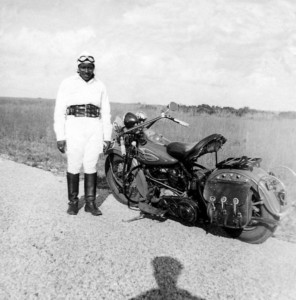

But is it so much more difficult today? Take the story of Bessie Stringfield, the African-American, Harley Davidson-loving female rider of the 1930s who, decades before the Civil Rights movement, rode across country countless times, and even entered men’s motorcycle races (only to be denied the winning prize when they found out she was a woman).

Pursuing her passion on two wheels in a country that made it nearly impossible for black citizens to move freely and where lynching was still legal in most of the towns she passed through, Bessie was putting her life in constant danger.

When motels refused her a room, which happened all too often, her Harley Davidson became her bed, her motorcycle jacket her pillow and gas station parking lots her hotel rooms. She recalled stories of being knocked off her motorbike by white men in pickup trucks and facing discrimination from road police.

Bessie Stringfield, Aka, the “Motorcycle Queen” of the 1930s

In spite of it all, Bessie travelled to every state in the country, as well as riding through Europe, Brazil and Haiti. She called them her “penny tours”– a ritual that involved tossing a penny onto an open map. Wherever it landed would be her next destination. Fear, apprehension or excuses, just didn’t even come into it.

But let’s go even further back in time and back to basics, when motorized bikes hadn’t yet entered the picture. In 1856, a Latvian Jewish American immigrant and free-thinking lady became the first woman to ride a bicycle around the world. Her name was Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, and later became known as “Annie Londonderry”. It all began with a bet, when two rich men from Boston wagered that no woman could travel around the world by bicycle.

Annie was probably the unlikeliest of women to take up the challenge, mostly because she had never ridden a bicycle until a few days before she began the journey. She was also a married mother of three very young children and a Jewish immigrant in a country where anti-Semitism was rampant. She managed to find a sponsor that paid her $100 to attach a placard advertising the Londonderry Lithia Spring Water company and agree to go by the name “Annie Londonderry” for the duration of her trip.

She set off from Beacon Hill Massachusetts and made it to Chicago where she upgraded her bicycle and traded a dress for men’s bloomers. She later boarded a French liner from New York to Le Havre, France where her bike and money were confiscated. Amidst bureaucratic sabotage and a disappointing turn of events, the French press began writing insulting articles about her appearance.

Eventually overcoming the setback, she rode from Paris to Marseille with one injured foot bandaged and propped up on her handlebars. Londonderry boarded a steamship to Sydney with just 8 months to get back to Chicago, visiting Alexandria, Sri Lanka, and India (where she hunted tigers with German royalty), Singapore, Saigon, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Nagasaki where she was allegedly sent to a Japanese prison with a bullet wound.

Annie sailed from Japan to San Francisco and road to Arizona at which point she was almost killed in an accident with a runaway horse and wagon, spending two days coughing up blood in a hospital. In Iowa, she broke her wrist after crashing into a group of pigs and wore a cast for the rest of the journey until she reached home in 1895. Londonderry collected her $10,000 prize and published an account of her exploits in the New York World under the headline “the Most Extraordinary Journey Ever Undertaken by a Woman”.

In a later article about her adventures as the “New Woman“, she wrote, “I am a journalist and a ‘new woman,’ if that term means that I believe I can do anything that any man can do.”

Messynessy