To regard all material improve ments as a move away from spirituality, or to assert that science, and the industries are based on it, is absolutely evil, is unfair and untrue.

The grim needs of war pushed technological advance ahead at an amazing speed. This advance may be used either to make us more materialistic or to make us less so. In itself it is neutral.

There is a line of connection which can be traced from the appearance of gentle Jesus to the terrors of the Inquisition. There is another line which can be traced from the work of pioneer scientists like Galileo and Bacon to the work of atomic scientists like Einstein and Oppenheimer.

If Jesus’ gospel was a message from God, science was a different kind of revelation from God. Both Inquisitional tortures and Hiroshima’s horrors are evidences of what men have done to the fine things entrusted to them. It is for the men themselves to undo their misdeeds and not wait for a Savior to do it. The responsibility is theirs.

It was the prevalence of superstition in all departments of human life, activity, belief, and thought which brought about the needed counter-culture of the exact sciences. But under the various superstitions there was not seldom some measure of covert fact and hidden truth. Science has itself become, because of its one-sided, self-made limitation, and through refusal to depart from materialistic views, a sort of superstition.

Technical skill, verified experiment, and laboratory research are necessary and valuable, but their presence ought not to be used as an excuse for abandoning everything else which ought to be considered.

Hence we witness today such evils as the pollution of nature and the poisoning of human nutriment. There is no other way out now than to compensate for the missing elements, to broaden culture in a basic way – a coexistence previously believed to be impossible.

Man looked into the mysteries of the atom when he was too selfish to use it rightly, too ignorant of the higher laws to use it wisely – that is, when he was unworthy and unready. He is in such danger today that many regret he ever did so. But he could not help it, could not have done otherwise.

The mind wants to know; this is its essential nature: it was inevitable that what began as simple childish curiosity should end as rigorous scientific investigation. Nothing could stop this process in the past.

This was the warning of Greek, European, and American history. It is now the warning of Chinese, Southeast Asian, and Indian history, where seemingly static civilizations become more dynamic.

When science serves politics only, and both are unguided by knowledge of the higher laws governing mankind, then both, in this age of nuclear weapons, put mankind in danger of nuclear annihilation.

Where the nineteenth-century Westerner displaced religion by science, the twentieth-century Westerner is increasingly being faced, through the unexpected results of nuclear science, with having to refind interest in religion, recover the truth in religious teaching, and regain the peace in religious experience.

The scientists conceived the atomic bomb, the heads of government financed it, and the military used it.

This was the triple combination which brought humanity to its present plight. Admittedly, they did this with the best intentions and under the stress of seeming outer necessity. But the fact still remains that it was they who created the danger for all of us and it is they who now seem unable to free us from it.

It is necessary for man to be reminded of his comparative nothingness when his intellect swells into dangerous arrogance. With the triumphs of atomic research and the gadgets of mechanical civilization, he has reached such a point.

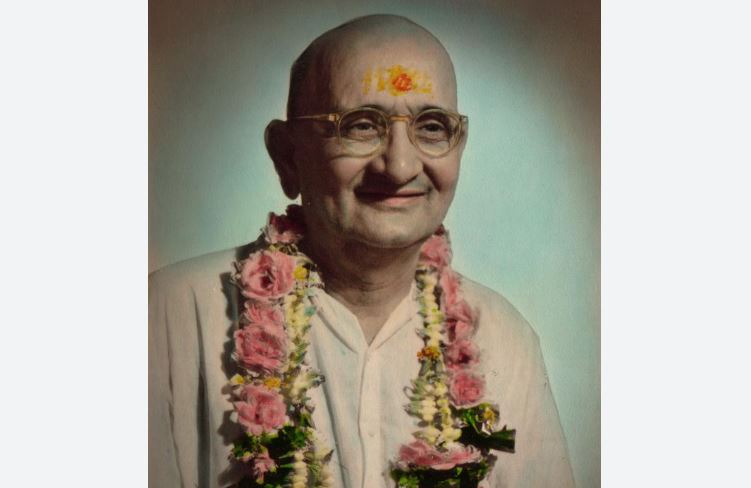

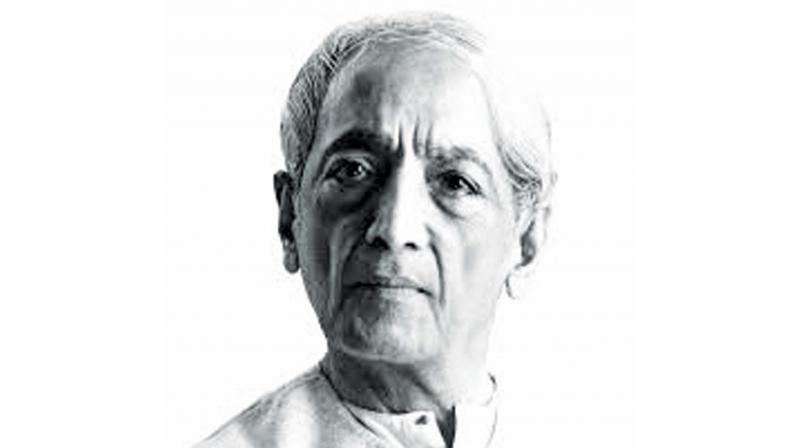

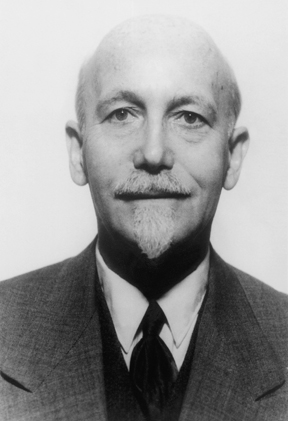

Excerpted from The Notebooks. The 117th birth anniversary of Paul Brunton was observed on October 21

Paul Brunton