MOUNTAIN VIEW, CA: “Merchant on Venice”, a repurposed appropriation of the Shakespearean “Merchant of Venice” was played out at the Mountain View Center for Performing Arts several weekends in November, 2014. A production by Enacte in its third year of existence, it aimed to promote and showcase South Asian talent.

MOUNTAIN VIEW, CA: “Merchant on Venice”, a repurposed appropriation of the Shakespearean “Merchant of Venice” was played out at the Mountain View Center for Performing Arts several weekends in November, 2014. A production by Enacte in its third year of existence, it aimed to promote and showcase South Asian talent.

The venue was pleasing, inviting and intimate, as the sparse audience settled down for an evening of versed dialogue with elements of old English play acting with masala overtones of Bollywood.

The opening scenes take a while to get the story going where the confused audience tries to figure out the parallels between the characters on stage and the known characters of Shakespeare’s play.

The quick introduction by director, Sonalee Hardikar, where it is made known that this is a bold re-imagination of the original, set in Culver City, on Venice Boulevard, did help somewhat, however, the lack of visual cues for the audience made for a bumpy start.

The dialogue-intense play required complete engagement which the audience was happy to give and was soon wrapped up in the story of love, betrayal, friendship, and a good dose of Bollywood elements complete with a song and dance sequence.

Jeetendra, played by Sonu Bains, the struggling actor, wants to impress his girlfriend, Pushpa, played by Angelica Shah, and thus needs to borrow some money. His good friend, Devendra, played by Amasalan Doraisingam (also a co-director) provides the collateral against his ships in order for the local moneylender, the Vohra Muslim Sharuk, well portrayed by thespian Vijay Rajvaidya, to loan the moneys.

Sharuk however, extracts the promise of emasculating Devendra and extracting “his ounce of flesh” upon failure to repay the loan. The plot essential to the story line thus established, moves on to introduce Pushpa as a movie director’s daughter, and Jeetendra’s love, who fields an array of suitors for her hand.

In a twist from the original ploy where the suitors had to pick the right one from a selection of three caskets to win the damsel’s hand, now have to choose between three DVDs of movies.

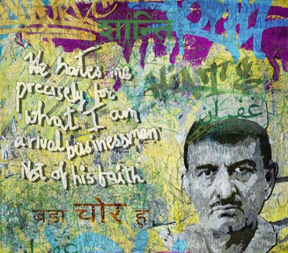

As the characters of Sharuk and Devendra are developed, we get to see the bone of contention between them being that of the age old Hindu-Muslim distrust. Sharuk’s many monologues, some of them lasting almost 5 minutes bring up a litany of unpleasantness committed in a far away land and centered on demonization of Muslims. Devendra, a religious bigot continues generalizing the Muslim stereotype much to Sharuk’s increasing rage.

A surprise entrant is the character of Tooranpoi, loosely based on Launcelot Gobbo, superbly played by Ranjita Chakravarty, who entertains more in the spirit of the Shakespearean clown, and thus is used as a vehicle to deliver politically incorrect and sensitive issues.

Tooranpoi’s mischievous and humorous antics lend an insight into his world, which is not always rosy, as he resents working for Sharuk, and flatters and convinces Jeetendra to hire him.

He reflects on his promised salary, and conveys a sense of the plight faced by low waged employees, finding work within dubious establishments away from their homeland. It is regrettable that this character was not returned in the second act.

Meanwhile, within Sharuk’s family, another betrayal is about to unfold….that of his daughter Noorani, played by Sukanya Chakrabarti, who chooses her own mate, and goes off in the sunset to seek her fortunes with him. A sweetly sung rendition emotes the soulful union of this young couple.

At the very same moment Sharuk is invited to break bread with Jeetendra and Devendra to seal the money lending deal. A rather interesting, but somewhat choppy introduction of a song and dance sequence incorporates the festival of Holi, with clever use of colorful duppattas to simulate the colors of Holi, that also underlines Sharuk’s reluctance to this meeting with the Hindus in the midst of this Hindu festival.

As the plot thickens with the loss of Devendra’s collateral, he faces the reality of losing his masculinity to keep his promise to Sharuk. The court trial scene, a well remembered and oft replayed piece of the original is presented as a farce, done mainly to humor Sharuk.

The lawyers, played by Pushpa, and her maid, Kavita, first dressed up in manly clothing, then made to change to Indian women’s garb, try to argue the lack of shedding blood as a key provision of this contract. A real twist comes in as Sharuk is ready to go ahead with his halal butcher who will be able to do just that. Devendra insists on honoring his promise and awaits his fate.

Sharuk emotes the conflict he feels at this moment, in which Noorani’s betrayal is greater than Devendra’s blasphemy. In his mind, Devendra’s complicity and perceived conspiracy takes the blame for the hurt he feels from his daughter’s actions. In the end, however, Sharuk is unable to follow through, and puts away his scalpel.

Kavita, who is played by Soma Mitra as Pushpa’s servant, pleads impassionately to mend relationships between Hindus and Muslims which further seals the non- action on Sharuk’s part.

The audience is grappling with this turn of events, as it is a huge departure from the known plot, and merits tighter and unambiguous direction. The redemption for Sharuk comes not from conversion to Hinduism, but to a much applauded division of his wealth to benefit the temple, his daughter and new son in law, and SABU (South Asian Business Unit).

In a conversation, the playwright Shishir Kurup mentioned that he conceived this play as an appropriation of the original. This makes sense as he stripped away the flesh of the original “Merchant of Venice”, keeping the bones intact; and re-layered it with the conflicts and issues in the South Asian context.

He was inspired by the location of the intersection of Venice Boulevard with Carrington Boulevard in Culver City, where he noticed a medley of shops and people of mixed South Asian descent. Thus his characters in this appropriation depict various sub cultures of the Indian Diaspora with sometimes mixed results.

The writing, direction, and acting of this play is a composite work with many pleasing, light hearted and unexpected turns, while conveying the seriousness of the continuing religious conflict. It is a well written play, with many a twist and liberties with the English language to suit the needs of its “Bollywoodization”, which provide the mirth and somberness of the issues at hand.

Archana Asthana

India Post News Service