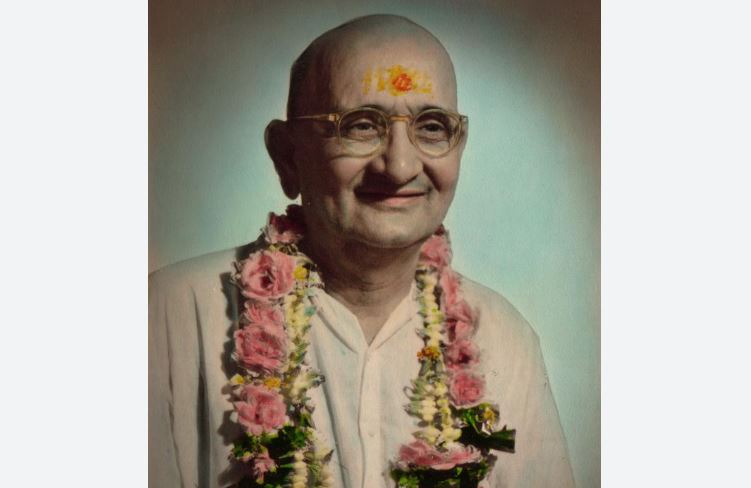

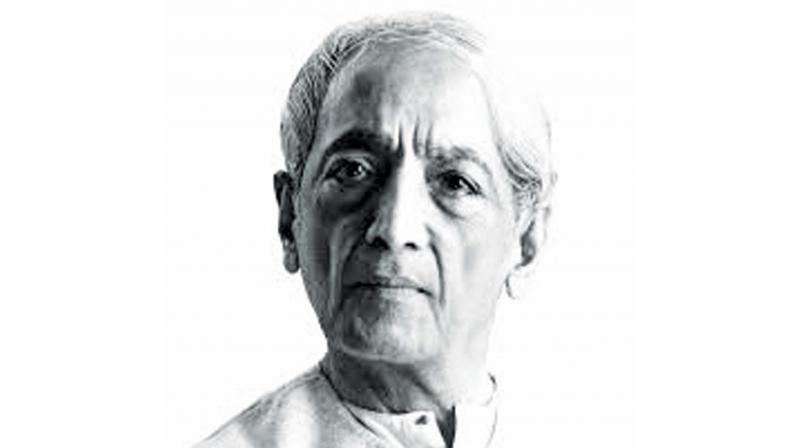

Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru

I have developed strange habits in prison. One of these is the habit of getting up very early — earlier even than the dawn. I began this last summer, for I liked to watch the coming of the dawn and the way it gradually put out the stars. Have you ever seen the moonlight before the dawn and the slow change today? Often I have watched this contest

between the moonlight and the dawn, in which the dawn always wins.

In the strange half-light it is difficult to say for some time whether it is the moonlight or the light of the coming day. And then almost suddenly there is no doubt of it and it is day, and the pale moon retires, beaten, from the contest.

According to my habit, I got up today when the stars were still out, and one could only guess that the morning was coming by that strange something which is in the air just before the dawn. And as I sat reading, the calm of the early morning was broken by distant voices and rumblings, ever growing stronger. I remembered that it was the Sankranti day, the first big day of the Magh Mela, and the pilgrims were marching in their thousands for their morning dip at the Sangam, where the Ganga meets the Jumna and the invisible Sarasvati is also supposed to join them. And as they marched they sang and sometimes cheered mother Ganga — Ganga Mai ki Jai — and their voices reached me over the walk of Naini Prison. As I listened to them I thought of the power of faith which drew these vast numbers to the river and made them forget for a while their poverty and misery. And I thought how year after year, for how many hundreds or thousands of years, the pilgrims had marched to the Triveni.

Men may come and men may go, and governments and empires may lord it awhile and then disappear into the past; but the old tradition continues, and generation after generation bows down to it.

Tradition has much of good in it, but sometimes it becomes a terrible burden, which makes it difficult for us to move forward. It is fascinating to think of the unbroken chain which connects us with the dim and distant past, to read accounts of these melas written 1300 years ago — and the mela was an old tradition even then. But this chain has a way of clinging on to us when we want to move on, and of making us almost prisoners in the grip of this tradition. We shall have to keep many of the links with our past, but we shall also have to break through the prison of tradition wherever it prevents us from our onward march.

Early history

We have one great difficulty in studying the early history of India. The early Aryans here— or the Indo-Aryans as they are called — cared to write no histories. The books they have produced — the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and other books — could only have been written by great men. These books and other material help us in studying past history. They tell us about the manners and customs, the ways of thinking and living of our ancestors. But they are not accurate history.

Excerpted from ‘Glimpses of World History’, a collection of letters to his daughter, Indira Priyadarshini, written in jail. The 125th birth anniversary of Jawharlal Nehru was is being observed on November 14