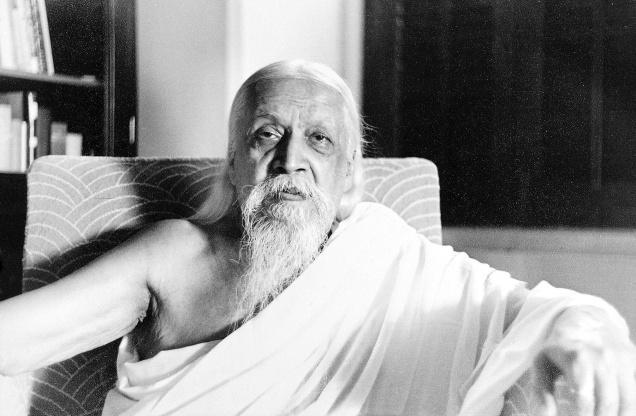

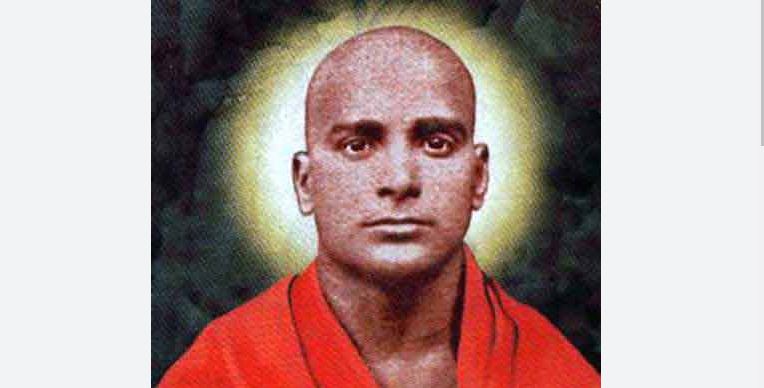

Sri Aurobindo

Our first step in this path of knowledge, having once determined in our intellect that what seems is not the Truth, that the self is not the body or life or mind, since these are only its forms, must be to set right our mind in its practical relation with the life and the body so that it may arrive at its own right relation with the Self. This it is easiest to do by creating a separation between the Prakriti and the Purusha.

The Purusha, the soul that knows and commands has got himself involved in the workings of his executive conscious force, so that he mistakes this physical working of it which we call the body for himself; he forgets his own nature as the soul that knows and commands; he believes his mind and soul to be subject to the law and working of the body.

He forgets that he is so much else besides that is greater than the physical form; he forgets that the mind is really greater than Matter and ought not to submit to its obscurations, reactions, habit of inertia, habit of incapacity; he forgets that he is more even than the mind, a Power which can raise the mental being above itself; that he is the Master, the Transcendent and it is not fit the Master should be enslaved to his own workings, the Transcendent imprisoned in a form which exists only as a trifle in its own being.

All this forgetfulness has to be cured by the Purusha remembering his own true nature and first by his remembering that the body is only working and only one working of Prakriti. We say then to the mind “This is a working of Prakriti, this is neither thyself nor myself; stand back from it.”

We shall find, if we try, that the mind has this power of detachment and can stand back from the body not only in the idea but in the act and as it were physically or rather vitally. This detachment of the mind must be strengthened by a certain attitude of indifference to the things of the body; we must not care essentially about its sleep or its waking, its movement or its rest, its pain or its pleasure, its health or ill-health, its vigor or its fatigue, its comfort or its discomfort, or what it eats or drinks.

This does not mean that we shall not keep the body in the right order so far as we can; we have not to fall into violent asceticisms or positive neglect of the physical frame. But we have not either to be affected in mind by hunger or thirst or discomfort or ill health or attach the importance which the physical and vital man attaches to the things of the body or indeed any but quite subordinate and purely instrumental importance.

Nor must this instrumental importance be allowed to assume the proportions of a necessity; we must not, for instance, imagine that the purity of the mind depends on the things we eat or drink, although during a certain stage restrictions in eating and drinking are useful to our inner progress; nor on the other hand must we continue to think that the dependence of the mind or even of the life on food and drink is anything more than a habit, a customary relation which Nature has set up between these principles.

Excerpted from ‘The Synthesis of Yoga’. The 147th birth anniversary of Sri Aurobindo is being observed on August 15